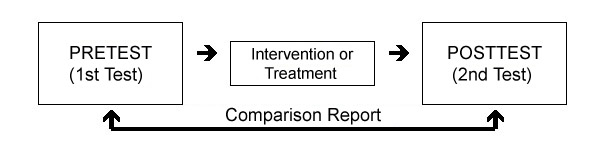

These four, treatment effectiveness tests are administered twice: At treatment intake (before treatment or pre-test) and, again, at treatment completion (post-test). The pre-test serves as a baseline for post-test comparison.

The intent here is to make test users, treatment staff and referral sources(e.g., courts, private practitioners, probation departments, clinicians, assessers and mental health providers) aware of Behavior Data Systems, Ltd. (BDS) treatment effectiveness or treatment outcome tests. BDS's Treatment outcome tests include:

U.S. courts adjudicate cases involving psychological issues dailiy. And judges may mandate treatment or treatment may be a condition or requirement of probation. And, mental health professionals treat or refer patients for treatment.

We have entered an era of treatment accountability. Historically, it was enough to know the client (patient/offender) completed their assigned treatment protocol. It was assumed when treatment (classes, meetings, counselings or psychotherapy) was completed the client was better. Research (Echardt, 2009, Mechanic el. al., 2000; and Bloom el. al., 2007) has shown that some, if not every clients, do not benefit from treatment. These findings underscore the need for objective evidence based treatment effectiveness or outcome measures.

Many people (courts, evaluators, treatment staff, probation departments, referral agencies, and others), including the patients and their families want to know if treatment was effective. And insurance carriers, managed cased administrators, state and county overseers, program managers, regulators, oversight committees, and tax payers also want to know if treatment was effective

Behavior Data Systems (BDS) outcome or treatment effectiveness tests are administered to a client (patient/offender) twice: once before treatment (pretest) and again after treatment (posttest). In other words, the same test is administered twice. Comparison of pretest and posttest differences is the main purpose of the Comparison Report.

Everybody that is aware of the client having been treated asks the same question, "Was treatment effective?" or "Did the client positively change?". BDS's treatment effectiveness or treatment outcome tests help answer these questions. To review a treatment effectiveness or treatment outcome test (and their Comparison Report) click on one of the following treatment effectiveness test links.

The Pretest-Posttest paradigm involves testing before and after treatment, with pre-post differences attributed to the intervening treatment. The pretest serves as a baseline for posttest comparison. Many mental health professionals, treatment staff, program administrators and others accept baseline theory and methodology, whereas others may not. If you don't accept baseline methodology, you should not use BDS's Treatment Effectiveness Tests.

The composition of BDS's Pre-Post Inventory scales (domains or measures) consists of eight scales (domains) and these are:

1. Truthfulness Scale

2. Anxiety Scale

3. Depression Scale

4. Distress Scale

5. Self-Esteem Scale

6. Alcohol Scale

7. Drug Scale

8. Stress Management Scale

These eight scales (domains) represent common outpatient referral problems, issues, and concerns in the Pre-Post Inventory. In contrast, the DVI Pre-Post consists of six scales (domains) and these are:

1. Truthfulness Scale

2. Violence Scale

3. Control Scale

4. Alcohol Scale

5. Drug Scale

6. Stress Management Scale

Continuing scale comparisons, the Probation Referral Outcome contains eight scales or domains and these are:

1. Truthfulness Scale

2. Depression Scale

3. Anxiety Scale

4. Violence Scale

5. Alcohol Scale

6. Drug Scale

7. Self-Esteem Scale

8. Stress Management Scale

And the one juvenile treatment effectiveness test is the Juvenile Pre-Post, which contains eight scales or domains:

1. Truthfulness Scale

2. Depression Scale

3. Anxiety Scale

4. Distress Scale

5. Alcohol Scale

6. Drug Scale

7. Self-Esteem Scale

8. Stress Management Scale

The Treatment Effectiveness Tests (DVI Pre-Post; Probation Referral Outcome; Pre-Post Inventory, and the Juvenile Pre-Post) described herein employs the same methodology. Each test is administered twice - before entering treatment and upon treatment completion. Pretest scale scores serve as a baseline for subsequent posttest comparison. These treatment effectiveness tests are multimodal (or multiscale) self-report assessment instruments or tests. Upon data (answers) computer input scored and printed reports are available within 3 minutes on-site. These treatment outcome tests provide a broad and relevant outcome spectrum for assuring treatment-related change.

In the past, patients and offenders were assumed to have been rehabilitated, cured or positively changed by virtue of having completed their assigned treatment. Recent research has shown this is not necessarily the case. Many clients (patients/offenders) do not benefit from treatment. These findings underscore the need for objective evidence based treatment outcome measures.

Everybody that is aware of client's (patients/offenders) completing their assigned treatment asks the same question, i.e, "Was treatment effective?" or "Did the client positively change?" To review a treatment effectiveness test's report click on the tests name (above). This also enables you to review that tests printed comparison report.

There are many terms that address the notion of truthfulness within the context of assessment, treatment and rehabilitation, including denial, problem minimization, misrepresentation, and equivocation. The prevalence of denial among patients, and offenders is, extensively, discussed in the psychological literature (Marshall, Thornton, Marshall, Fernandez, & Mann, 2001; Brake & Shannon, 1997; Barbaree, 1991; Schlank & Shaw, 1996).

The impact the Truthfulness Scale score has on other scale or test scores is contingent upon the severity of denial, or untruthfulness. In assessment, socially-desirable responding impacts assessment results, when respondents attempt to portray themselves in an overly favorable light (Blanchett, Robinson, Alksnis & Sarin, 1997).

Awareness of truthfulness scales (measures) increased with the release of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), almost six decades ago. Soon thereafter, socially-desirable responding was demonstrated to impact assessment results (Stoeber, 2001; McBurney, 1994; Alexander, Somerfield & Ensminger, 1993; Paulhus, 1991). Truthfulness Scale conceptualization began, in earnest, with the idea of self-response accuracy.

Test users wanted to be sure that respondents’ (patients, offenders) self-report answers were truthful. Evaluators and assessors need to know if they can rely upon the test data being accurate. In other words, can the respondent’s (patients, offenders) self-report answers be trusted? Research also shows that truthfulness is a factor in diagnosis, treatment effectiveness, and recidivism. Because denial is thought to be an important component of assessment and rehabilitative outcomes, various measures have been developed to augment identification (Schneider & Wright, 2001; Eccles, Stringer, & Marshall, 1997).

While some assessments focus on general truthfulness (denial), and others are specific to an offense or problem (Tierney & McCabe, 2001), before denial can be addressed and worked through, it must first be identified. And, that’s where Behavior Data Systems (BDS) Truthfulness Scales fit in. They determine client (patient/offender) truthfulness while completing BDS tests.

Client (patient or offender) truthfulness has been associated with more, positive treatment outcomes (Barber, et. al., 2001; Simpson 2004).

Problem minimization has also been linked to lack of treatment progress (Murphy & Baxter, 1997); treatment dropout (Daly & Peloski, 2000; Evans, Libo & Hser, 2009); and offender recidivism (Nunes, Hanson, Firestone, Moulden, Greenberg & Bradford, 2007; Kropp, Hart, Webster & Eaves, 1995; Grann & Wedin, 2002). Some researchers (Baldwin & Roys, 1998; Grossman & Cavanaugh, 1990 Haywood & Grossman, 1994; Haywood, Grossman & Hardy, 1993; Nugent & Kroner, 1996; Sefarbi, 1990) have suggested that client denial should be eliminated, prior to commencing treatment; whereas, others argue that offenders should not be excluded from starting treatment due to their denial (Maletzky, 1996). Despite different views on the role of denial at treatment intake, reductions in denial are associated with increased likelihood of treatment success (O’Donohue & Letourneau, 1993).

Invariably, assessors (evaluators, test users) must answer the questions, “Was the client (patient, offender) truthful while being tested? Can we rely on the test results?” Evidence-based truthfulness scales answer these questions.

The "interview" has been the mainstay in evaluations for many years, despite its paradoxical lack of reliability, validity, and accuracy. Most mental health professionals agree that the interview has not been a good predictive instrument, and that it is, notoriously, time consuming. Most practitioners believe the interview, by itself, does not present a defensible basis for making diagnostic and treatment decisions. Interviews are prone to error and the reasons are many, owing to diversity in interviewer personalities and in training and equivocal motivation. Interviewers must repeat, paraphrase, and probe for scoreable answers, thereby introducing subjectivity and error.

As multidimensional as denial is (Barrett, Sykes, & Byrnes, 1986; Brake & Shannon, 1997; Happel & Auffrey, 1995; Laflen & Sturm, 1994; Langevin, 1988; Orlando, 1998; Salter, 1988; Trepper & Barrett, 1989), truthfulness is equally multifaceted. Yet, client truthfulness (and denial) is integral to accurate assessment, testing, and evaluation, and to effective treatment and rehabilitation. Consequently, truthfulness will continue to be studied in the future.

Behavior Data System (BDS) and its subsidiaries, Risk & Needs Assessment, Inc. and Professional Online Testing Solutions, Inc., have their own, individualized Truthfulness Scales. These Truthfulness Scales consist of approximately, twenty test items. And, each Truthfulness Scale has impressive, evidence-based reliability, validity, and accuracy. Truthfulness Scale research is reported in www.BDS-Reserch.com.

Alexander, C., Somerfield, M., Ensminger, M., et al. (1993). Consistency of adolescents’ self-report of sexual behavior in a longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence; 25, 1379-95.

Baldwin, K., & Roys, D. T. (1998). Factors associated with denial in a sample of alleged adult sexual offenders. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 10(3), 211-226.

Barbaree, H. E. (1991). Denial and minimization among sex offenders: Assessment and treatment outcome. Forum on Corrections Research, 3, 30-33.

Barber, J., Luborsky, L., Gallop, R., Crits-Christoph, P., Frank, A., Weiss, R., Thase, M., Connolly, M., Gladis, M., Foltz, C., Siqueland, L. (2001). Therapeutic alliance as a predictor of outcome and retention in the National Institute on Drug Abuse Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 2001; 69(1):119–124.

Barrett, M. J., Sykes, C., & Byrnes, W. (1986). A systemic model for the treatment of intra-family child sexual abuse. In T. Trepper & M. J. Barrett (Eds.), Treating incest: A multiple systems perspective (pp. 67-82). New York: Haworth.

Blanchette, K. Robinson, D., Alksnis, C., Serin, R. (1997). Assessing Treatment Outcome Among Family Violence Offenders: Reliability and Validity of a Domestic Violence Treatment Assessment Battery. Ottawa: Research Branch, Correctional Service Canada.

Brake, S. & Shannon, D. (1997). Using pretreatment to increase admission in sex offenders. In B. K. Schwartz & H. R. Cellini (Eds.), The sex offender: New insights, treatment innovations and legal developments, Volume 2 (pp.5-1–5-16). Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute.

Daly, J. & Pelowski, S. (2000). Predictors of dropout among men who batter: A review of studies with implications for research and practice. Violence and Victims, 15, 137-160. [Abstract].

Eccles, A., Stringer, A., & Marshall, W. L. (1997, October). Denial and minimization in sexual offenders: A self-report measure. Poster presented at the 16th Annual Research and Treatment Conference of the Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers, Crystal City, VA.

Evans, E. Libo, L. Hser, Y. (2009). Client and program factors associated with dropout from court-mandated drug treatment. Eval Program Plann. 2009 August; 32 (3) 204-212.

Gibbons, P., Volder, J. & Casey, P. (2003). Patterns of Denial in Sex Offenders: A Replication Study. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 31: 331-44.

Grann, M. & Wedin, I. (2002). Risk factors for recidivism among spousal assault and spousal homicide offenders. Psychology, Crime, and Law, 8, 5-23.

Grossman, L., & Cavanaugh, J. (1990). Psychopathology and denial in alleged sex offenders. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 178(12), 739-744.

Happel, R. M., & Auffrey, J. J. (1995). Sex offender assessment: Interrupting the dance of denial. American Journal of Forensic Psychology, 13(2), 5-22.

Haywood, T., & Grossman, L. (1994). Denial of deviant sexual arousal and psychopathology in child molesters. Behavior Therapy, 25(2), 327-340.

Haywood, T., Grossman, L., & Hardy, D. (1993).Denial and social desirability in clinical examinations of alleged sex offenders. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 181(3), 183-188.

Khandaker, R. (2010). Sexual Adjustment Inventory: An Inventory of Scientific Findings. Behavior Data Systems, Ltd.

Kropp, P. R., Hart, S. D., Webster, C. D., & Eaves, D. (1995). Manual for the Spousal Assault Risk Assessment Guide (2nd ed.). Vancouver, Canada: B.C. Institute on Family Violence.

Laflen, B., & Sturm, W. R., Jr. (1994). Understanding and working with denial in sexual offenders. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 3(4), 19-36.

Langevin, R. (1988). Defensiveness in sex offenders. In R. Rogers (Ed.), Clinical assessment of malingering and deception (pp. 269-290). New York: Guilford.

Maletsky, B. M. (1996). Denial of treatment or treatment of denial? Sexual Abuse : A Journal of Research and Treatment, 8(1), 1-5.

Marshall, W. L., & Eccles, A. (1991). Issues in clinical practice with sex offenders. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 6(1), 68-93.

Marshall, W., Thornton, D., Marshall, L., Fernandez, Y., & Mann, R. (2001). Treatment of sexual offenders who are in categorical denial: A pilot project. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 13(3), 205-215.

McBurney D., (1994) Research Methods. Brooks/Cole, Pacific Grove, California.

Murphy, C. & Baxter, V. (1997). Motivating batterers to change in the treatment context. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 12, 607-619.

Newsome, R. & Ditzler, T. (1993). Assessing alcoholic denial. Further examination of the Denial Rating Scale. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 1993; 181(11): 689-94.

Nugent, P. & Kroner, D. (1996). Denial, response styles, and admittance of offenses among child molesters and rapists. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 11(4), 475-486.

Nunes, K., Hanson, R., Firestone, P., Moulden, H., Greenberg, D., Bradford, J. (2007). Denial predicts recidivism for some sexual offenders. Sex Abuse, 19 (2): 91-105.

O'Donohue, W., & Letourneau, E. (1993). A brief group treatment for the modification of denial in child sexual abusers: outcome and follow-up. Child Abuse & Neglect , 17 (2), 299-304.

Orlando, D. (1998, September). Sex offenders. Special Needs Offenders Bulletin, No. 3. Washington, D.C.: Federal Judicial Center.

Paulhus, D. (1991). Measurement and control of response biases. In J. P. Robinson et al. (Eds.), Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes. San Diego: Academic Press

Salter, A. C. (1988). Treating child sex offenders and victims. London: Sage.

Schlank, A. & Shaw, T. (1996). Treating sexual offenders who deny their guilt: A pilot study. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 8(1), 17-23.

Schneider, S. L., & Wright, R. C. (2001). The FoSOD: A measurement tool for reconceptualizing

the role of denial in child molesters. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 16, 545-564.

Schneider, S. & Wright, R. (2004). Understanding Denial in Sexual Offenders: A review of cognitive and motivational processes to avoid responsibility. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, Vol. 5 (1); 3-20. Sage Publications.

Sciacca, K. (1997). Removing barriers: dual diagnosis and motivational interviewing. Professional Counselor, 12(1): 41-6. Retrieved from: here

Sefarbi, R. (1990). Admitters and deniers among adolescent sex offenders and their families: A preliminary study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 60(3), 460-465.

Simpson D. (2004). A conceptual framework for drug abuse treatment process and outcomes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 2004; 27(2):99–121.

Stoeber, J. (2001). The social desirability scale-17 (SD-17). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 17, 222-232.

Tierney, D. & McCabe, M. (2001). The Assessment of Denial, Cognitive Distortions, and Victim Empathy among Pedophilic Sex Offenders, An Evaluation of the Utility of Self-Report Measures. Trauma Violence Abuse, 2 (3): 259-270.

Trepper, T., & Barrett, M. J. (1989). Systemic treatment of incest: A therapeutic handbook. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Winn, M. E. (1996). The strategic and systematic management of denial in the cognitive/behavioral treatment of sexual offenders. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 8(1), 25-36.

Test cost is another important factor in test selection. Behavior Data Systems, Ltd. (BDS) and its subsidiaries Risk & Needs Assessment, Inc. (Risk & Needs) and Professional Online Testing Solutions, Inc. (Online Testing) have the same price structure. The test unit fee is $9.95 per test.

By acting now you lock-in this low $9.95 rate for the entire term of your BDS test usage — even if the price of BDS tests should go up. In other words, you will enjoy absolutely guaranteed ironclad rate protection. Volume discounts are available.

Some testing companies employ á la carte billing which can be misleading. In these instances a test's cost is kept deceptively low. Then, when testing materials, test updates, research, accountability and support services are added, the test is much more expensive than originally quoted. Another stratagem for keeping a test’s cost low (e.g., very inexpensive or free testing) is not to provide many (or any) test-related services (e.g., lack of accountability, nobody standing behind or supporting the test if challenged, no ongoing research or upgrades). In other words, no support services are provided. In contrast, BDS and its subsidiaries charge one low and all-inclusive test fee of $9.95 per test, which includes everything listed below.

BDS and its subsidiaries (Risk & Needs and Online Testing) charge $9.95 per test and this fee incorporates all of the following free test-related items and services. Volume discounts are also available.

Individuals, agencies, departments, groups, corporations and high volume providers that purchase 800 or more tests a year are entitled to volume discounts. And, statewide or department testing programs qualify for an additional discount.

*Treatment effectiveness (or outcome) tests involve two test administrations of the same test (pretest and posttest). Treatment effectiveness or outcome tests cost $7.95 per test administration. In other words, the pretest costs $7.95, and separately posttests cost $7.95. These reduced prices are a professional courtesy acknowledging the two test administrations and cost.